American academic freedom is in danger, and it's a global issue

Interview with sociologist Michel Dubois

Since Donald Trump's return to the White House, the American scientific community has been facing an unprecedented offensive: massive removal of online content, budget cuts, layoffs, and self-censorship. Between funding reductions and the rewriting of reality by eliminating certain terms, what are the consequences for research? In this interview, sociologist Michel Dubois analyzes the mechanisms at play and the emerging resistance against this attack on scientific independence.

Can you detail these mechanisms and their impacts on the scientific community?

Michel Dubois : Since Donald Trump's return to the White House, the scientific and academic community has been facing a systematic offensive. At the federal agency level, operating budgets are being cut, federal employees are being laid off by the thousands, and regulatory frameworks that constrain economic and industrial activities are being dismantled. Under Trump’s directive, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced the freezing of research funds and the closure of the Office of Environmental Justice and Civil Rights.

But this offensive is not solely economic. It is also based on the idea that universities and research organizations are ideological adversaries. The aim is to challenge their claimed monopoly on defining what is true and what is not.

In figures

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) have laid off 1,200 employees

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has cut 10% of its workforce

- NASA has announced the closure of 3 of its departments

- $400 million in federal grants have been withdrawn from Columbia University

- 8,000 public web pages have been taken down

(source : lemonde.fr)

What is the objective behind this massive removal of scientific data and publications?

M. D. : The Trump administration’s primary objective is to “trim down” the federal government as much as possible. The major tech entrepreneurs who were invited to the January 20th inauguration ceremony are steeped in a libertarian culture that promotes the free market and individual innovation. That doesn’t stop them, however, from seeking public funding or collaborating with the state for lucrative contracts.

Another objective is to render invisible certain aspects of reality that are deemed problematic. The list of discouraged words maps out the version of reality the Trump administration refuses to acknowledge. Excluding words like “diversity,” “equity,” and “inclusion” seeks to suppress any discourse promoting inclusivity and fairness. Banning terms such as “gender,” “non-binary,” and “transgender” aims to restrict the recognition of gender identities and the rights of transgender and non-binary individuals. Similarly, prohibiting words like “racism,” “oppression,” or “systemic” signals a desire to prevent the study of inequalities and the impact of social structures on discrimination. Removing terms such as “health disparity,” “trauma,” and “vulnerable populations” minimizes awareness of health inequalities, particularly those affecting marginalized groups. Finally, censoring words like “climate crisis,” “clean energy,” and “pollution” reflects the Trump administration’s climate denialism, aligned with fossil fuel industry interests.

Trump’s techno-scientific agenda is clearly pro-business, as seen in the composition of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), which includes Michael Kratsios and David Sacks — both with business backgrounds. But what’s happening now goes far beyond business as usual: it’s about restricting scientists’ and experts’ capacity to produce independent knowledge, shaping the ideological framework of public debate by controlling access to data and information, and — if possible — further marginalizing already vulnerable social groups while limiting the study of inequalities.

What are the direct consequences of this political interference on research in climate science, public health, or the social sciences for American citizens?

M. D. : Funding cuts, data manipulation, weakened agencies, ideological pressure... In just a few months, these measures will have long-term impacts on society. Robert Kennedy, the new Health Secretary and a vaccine skeptic, recently promoted cod liver oil as a remedy for the measles outbreak in Texas. At the end of January, a North Dakota Senate bill proposed mandating the teaching of intelligent design in primary and secondary schools. In early February, legislators in Montana drafted a bill to ban mRNA vaccines in humans. At the end of February, the new Secretary of Energy, Chris Wright, stated that global warming could have positive effects. The list of these loosely coordinated disinformation campaigns is already long — and it's very likely that, in the medium term, they will expose the most vulnerable segments of the American population to increased health risks while fueling growing polarization of public opinion about science.

Can this situation be compared to other historical periods when science was attacked by political power?

M. D. : If we stick to U.S. history, the comparison with the McCarthy era is tempting. Trump and Vance’s ideological battle against so-called “wokeness” in universities parallels the earlier battle against communism. The list of banned words recalls that of “subversive” individuals who were placed under surveillance. In both cases, there is a clear politicization of science.

But the scientific community of the 2020s is not the same as that of the 1950s — and most importantly, whereas certain domains were particularly targeted in the 1950s, notably nuclear physics, today it’s hard to say which field of research is spared from the current offensive.

Many of the arguments voiced today by those supporting Trump’s techno-scientific agenda reveal a deep misunderstanding of how research actually works.

How is the American scientific community responding to these attacks and political interference?

M. D. : The scientific community had some time to prepare for Trump’s return, particularly by archiving large volumes of online data. In 2021, the Biden administration created an interagency task force on scientific integrity to address the issue of scientific independence. We owe to their efforts the recent and successive revisions of scientific integrity policies at the National Science Foundation (February 2024), NASA (May 2024), the National Institutes of Health (September 2024), and the Environmental Protection Agency (January 2025).

Despite these efforts, the initial reaction was one of shock at the scale of the offensive. Nearly two months after Trump’s return to the White House, the mood seems to be shifting toward mobilization. The Silencing Science Tracker, which has meticulously documented threats to scientific independence and integrity since 2016, has resumed its work. The “Stand Up for Science” protest on March 7 drew a solid turnout, including prominent figures like Francis Collins — recently removed from the NIH — who attended the demonstration in Washington, D.C.

However, we’re not yet seeing the same level of mobilization as during Trump’s first term. This more muted response may stem from a widespread climate of fear: many scientists today feel like they’ve been sitting on an ejector seat ever since the former president was re-elected.

You were a researcher in the United States during Trump’s first term. Were you already noticing these trends back then?

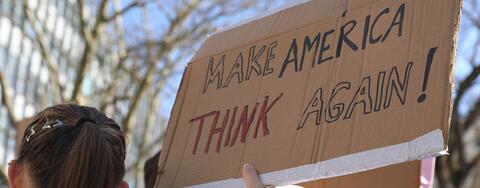

M. D. : Between 2016 and 2019, I was deputy director of an international and interdisciplinary CNRS laboratory — first in Los Angeles in collaboration with UCLA, then in Washington, D.C., with George Washington University. It’s important to remember that in 2016, Trump’s election caught everyone off guard — including Trump himself. That shock triggered a wave of mobilization. Like many of my colleagues, I took part in the March for Science in April 2017 in the streets of Los Angeles — a very festive and creative event, full of witty protest slogans.

Marche pour les sciences du 22 avril 2017 aux USA ©Michel Dubois

But in truth, at the start of its first term, the Trump administration didn’t have a clear agenda for science and technology. It was only later, when we relocated our laboratory to Washington, D.C., in the summer of 2018, that we began to observe the practices that have now become widespread: lists of banned words, budget freezes, and systematic disinformation. And perhaps most troubling of all, there was a strong institutional push toward self-censorship.

In that context, we were nevertheless able to collaborate with colleagues at the National Human Genome Research Institute, as well as with the French Embassy’s services, to organize scientific events in “diplomatic” spaces — thereby easing, at least partially, the pressure being exerted on academic freedom. Today, I believe it’s important to continue maintaining a European, and particularly French, research presence on American soil through this type of initiative.

What could be the consequences of these policies for research in Europe, and how can Europe respond?

M. D. : Scientific research knows no borders, and what is happening today at the NIH or Columbia University will have repercussions far beyond the United States. To focus on France and a few examples: we collaborate with American teams in areas as diverse as fundamental physics, astrophysics, climate science, biomedical research, space imaging and remote sensing, agronomy and plant biotechnology, and the social sciences. Some of these collaborations are already being impacted by budget freezes.

While individual universities welcoming colleagues who can no longer work in the U.S. is useful, what we really need is a coordinated Europe-wide initiative for hosting displaced researchers. As I pointed out in an op-ed in early February, Europe cannot simply stand by as a spectator. Despite its internal divisions, it must speak with one voice to support the research and higher education institutions in the United States that are fighting to preserve their independence in the face of political interference.

In that respect, the statement released in February by the European Federation of Academies of Sciences marks a first step in the right direction. Other initiatives are also beginning to take shape at the European level. Thirteen EU member states have already called on the Commission to take “immediate action” to welcome endangered researchers into Europe.