From Stone to Pixels: Digitizing the Decor of Notre-Dame de Paris

For the past three years, a multidisciplinary team has been using cutting-edge technology and historical expertise to unveil the mysteries of Notre-Dame de Paris.

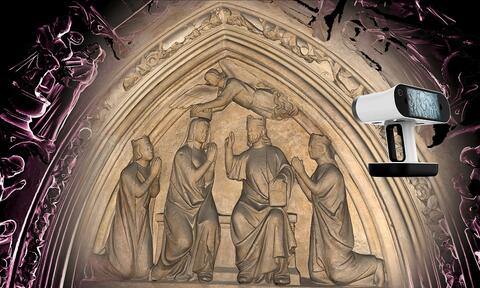

Under the coordination of Dany Sandron, a professor of art history and archaeology at Sorbonne University, the "Decor" group utilizes 3D scanning to analyze the cathedral's architecture and decoration. By bringing hidden details of the cathedral to life, the researchers are opening a new chapter in heritage studies, employing techniques that could inspire future restorations.

A Relatively Preserved Interior Decor

“I’ve been working on Notre-Dame for more than 20 years,” explains Dany Sandron. A specialist in medieval architecture and monumental decor, this professor of art history and archaeology at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities coordinates the Decor group within Notre-Dame’s scientific project. Since 2021, this group has brought together around fifteen international art historians and conservators. Thanks to the Plemo 3D platform he co-founded and the technical resources deployed over the past three years, Sandron’s team has been able to survey much of the cathedral’s decor.

“Fortunately, despite the extent of the fire, the interior decor was largely preserved, including fragile objects like the organ, paintings, and tapestries, which, after decontamination, remain intact,” says the researcher.

Mobile 3D Scanning and Modeling Platform (Plemo 3D)

PLEMO 3D is a platform of advanced digital equipment and tools, established in 2015 by the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at Sorbonne University in partnership with the University of Technology of Compiègne.

The platform is also open to external collaborations with regional authorities, museums, archaeological operators, construction companies, architectural firms, and others, enabling the promote the heritage of our buildings through high-value scientific digitization and modeling.

Technology in Service of History

Before the fire, the interior of the building was already blackened by dust and pollution, obscuring details of the sculpted elements located high above. Starting in 2021, scaffolding erected for restoration work allowed researchers to approach previously inaccessible decorative tops of columns and undertake their digitization.

“We used 3D photogrammetry to quickly create models. This technique involves capturing a multitude of images around objects. Software then analyzes these images, identifying common points to generate a 3D model. This model is subsequently textured and colored based on the initial photographs,” explains Grégory Chaumet, a PhD art history and Plemo 3D engineer.

To complement this approach, researchers employed another technique: lasergrammetry. Using a laser scanner that operates wirelessly, they had greater mobility for scanning complex objects, such as decorations ranging from a few centimeters to 1.5 meters in diameter. Over three years, Grégory Chaumet and postdoctoral researcher Denis Hayot scanned more than 300 decorative column tops, along with other sculptural elements. This work required the team to adapt to the logistical constraints of the restoration site while juggling the demands of other parallel research projects undertaken by Plemo 3D.

Modèle 3D d'un buste situé dans le transept nord de la cathédrale Notre-Dame issu de la numérisation par photogrammétrie ©Denis Hayot

Unexpected Discoveries

Digital surveys of the cathedral’s decor have revealed tool marks and assembly traces, providing invisible clues about the building’s construction. For example, researchers observed that in the monument’s choir, the oldest columns integrate the astragal—a molding at the base of decoration—into the same stone block as the column itself.

“This is a technique typical of ancient architecture,” says Dany Sandron.

This rare observation in medieval constructions challenges the notion of a break between Antiquity and the Middle Ages. “We thought the Middle Ages had severed ties with ancient knowledge, but these findings reveal a continuity of techniques and influences,” he adds. “This offers a more enlightened and nuanced view of the Middle Ages, often negatively portrayed. It’s essential to understand that historical periods don’t change abruptly, and there’s never a complete break, as is often assumed with major artistic movements,” the researcher explains.

Although access to the cathedral is now restricted for the final phase of reopening preparations, the team is determined to continue its research. “We’ll be able to resume work after the reopening, in a few months, during the restoration of the cathedral’s exterior,” assures Dany Sandron. This final restoration phase will focus on rebuilding the flying buttresses, which were already in poor condition before the fire.

Long-Term Multidisciplinary Research

To continue unraveling Notre-Dame’s secrets, the researchers collaborate with other teams, such as those from Sorbonne University’s Faculty of Science and Engineering and other French and international institutions, including the Historical Monuments Research Laboratory.

“There is genuine interdisciplinarity, with heritage professionals working alongside geologists, chemists, physicists, historians, and others,” says the researcher.

“We’ve also collaborated with Sorbonne University’s FabLab to create a 3D-printed segment of a capital from laser scanner surveys,” adds Grégory Chaumet.

A project to establish a permanent national thematic multidisciplinary network modeled on Notre-Dame’s scientific restoration initiative is currently under evaluation. This network would bring together complementary scientific and restoration expertise with specialized working groups on topics like decor and stained glass. “If we work on a cathedral like Reims or Amiens, which have even more imposing portals than Notre-Dame, it would be a shame not to leverage the expertise gained over the past five years,” emphasizes Dany Sandron.

Prise de mesures sur le modèle Modèle 3D d'un chapiteau de la cathédrale Notre-Dame issu de la numérisation par scanner laser ©Grégory Chaumet)

Making Research Accessible to the Public

Another way researchers are showcasing their work on Notre-Dame is through collaboration with the "Models and Simulations for Architecture and Heritage" Laboratory (CNRS/Ministry of Culture), which is developing a “digital twin” of the cathedral.

“Their European project aims to create a digital replica of the building, incorporating vast amounts of data such as written archives, photographs, and digital surveys, to make it accessible and consultable by the public,” explains Dany Sandron.

Some of the 3D models of Notre-Dame’s decor created by the team were featured in an exhibition at Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi about the cathedral’s scientific restoration.

“These scans and models will also be reused for Notre-Dame’s future museum, planned for part of the Hôtel-Dieu premises. Discussions are underway under the direction of the president of the National Heritage Institute,” says Dany Sandron. The future museum is expected to include both physical works and virtual reconstructions and interactive elements. “The idea is to use new technologies, like scans and holograms, to recreate damaged or missing works, offering a comprehensive view of the cathedral’s history and architecture. This approach is particularly useful for decorative fragments that are challenging to interpret in their current state,” highlights the researcher.

As Notre-Dame prepares to reopen its doors, the digital tools and innovative approaches experimented on this restoration project may well mark the beginning of a new era for heritage study and preservation. In just a few years, this cathedral, a symbol of resilience, has become a living laboratory where technology and history intertwine to reveal ancient craftsmanship and inspire future methods.