From the Middle Ages: Reconstructing the Cathedral

Maxime Fulconis, Sorbonne Université

After the shock of seeing Notre-Dame de Paris ablaze, experts and the public alike are questioning the best way to rebuild the cathedral. While it seems obvious to most that the external appearance of the roof should remain the same, debates arise about whether the internal framework should be reconstructed in metal or wood, and if so, using which methods? Similarly, the use of lead or a less toxic metal for the roof covering is under discussion. The main question, however, concerns the spire: should it be reconstructed identically, or should a contemporary interpretation be embraced?

In the Middle Ages, people frequently rebuilt their cathedrals, but they rarely posed these kinds of questions. Does this difference reflect a fundamental change in how we perceive these buildings?

Cathedrals in Motion

In our modern mindset, shaped by the concept of heritage, cathedrals are seen as unique structures meant to retain their material form and location forever. However, in the Middle Ages, people had no issue with moving a cathedral. For them, the building mattered less than the bishop’s throne (cathedra), which gave the cathedral its name. A cathedral was, above all, the church chosen by the bishop as the seat of his authority, both literal and figurative.

A bishop could decide to relocate the cathedral, which happened multiple times in the history of some cities. Take the example of Orvieto, a city between Rome and Florence. In late antiquity, the cathedral’s seat was located in a church dedicated to Saint Andrew at the heart of the city. Around the 7th century, the bishop moved the cathedral to a smaller church outside the city walls. By the mid-11th century, the cathedral was relocated back inside the city, but rather than returning to the church of Saint Andrew, a new modest church was founded and dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

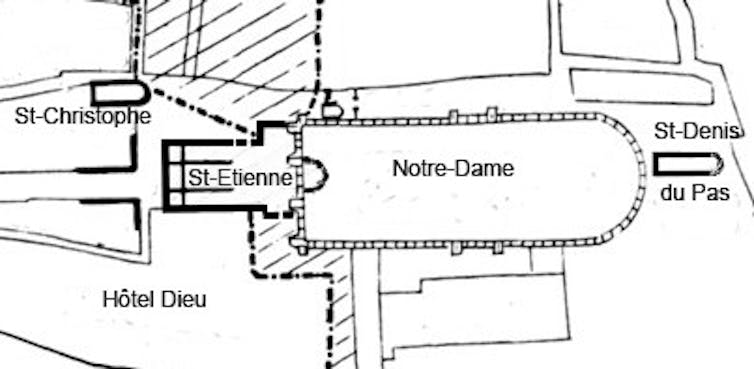

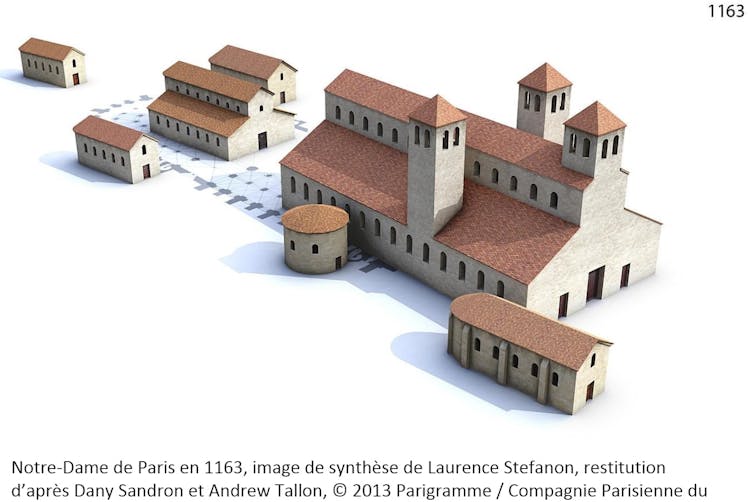

The dedication of cathedrals to the Virgin became typical in the 11th and 12th centuries, as cathedrals of the early Middle Ages were often dedicated to prominent martyrs. In Paris, for instance, the early medieval cathedral was dedicated to Saint Stephen between the 4th century and the 1160s. This earlier Parisian cathedral was not located where Notre-Dame stands today but slightly to the front of it. Visitors to the archaeological crypt can still see remnants of Saint Stephen’s cathedral. When Notre-Dame was built, the foundations of Saint Stephen’s rear wall were reused as the foundation for the new cathedral’s facade.

RRebuilding in a Completely Different Way

Unlike us, medieval builders rarely sought to replicate past forms when reconstructing a building. They almost always built in the style of their time, often showing a strong preference for novelty.

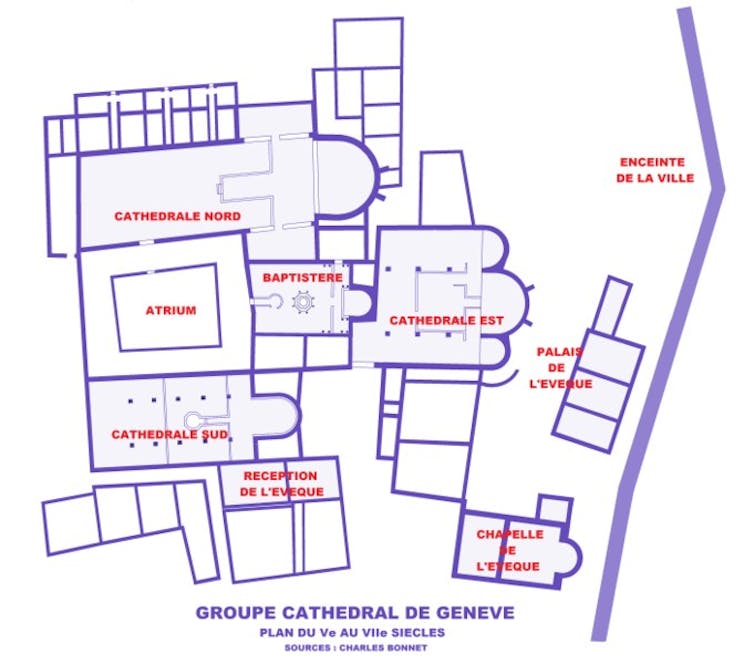

Returning to the example of Orvieto: when the cathedral was moved back to the city in the mid-11th century, it was constructed in the Romanesque style typical of the era. In reality, the cathedral was not a single building but a complex referred to as the "cathedral group." This included the cathedral itself, the bishop’s palace, a baptistery, a canons’ church, and ancillary buildings such as cloisters, refectories, and workshops. This arrangement, common in the Middle Ages, might seem unusual today but was standard at the time.

For those living in the early Middle Ages, a cathedral didn’t need to stand out architecturally. Often, it wasn’t even the largest or most beautiful church in the city. Starting in the 12th century in France and the 13th century in Italy, however, economic growth allowed for ambitious projects to rebuild monumental cathedrals. During these projects, builders made radical decisions: in Paris and Orvieto, they demolished the old cathedral and its dependencies to construct entirely new buildings with vastly different plans, dimensions, and sculptural programs. This era gave rise to the great Gothic cathedrals, designed as unique and majestic structures.

Between Maintenance and Transformation

Even when the grand architectural plans of the initial builders were followed, cathedral construction often spanned decades or even centuries. Successive architects and builders frequently modified original plans, sometimes enlarging the structures or redesigning facades and sculptural elements to reflect contemporary tastes.

Even once walls and frameworks were completed, cathedrals were never truly finished. Roofs were periodically replaced, and other structural elements were often rebuilt using newer techniques or styles. Decorative elements were added or altered: statues appeared on facades or roofs, mosaics and paintings were updated, and new chapels were constructed. For example, Notre-Dame was structurally completed around 1250, but in the 14th century, a wooden choir screen and numerous statues and altars were added.

Cathedrals were never static monuments but constantly evolving structures. This dynamic nature explains why so many churches today appear as patchworks, blending elements from various historical periods—Roman columns, early Christian mosaics, Romanesque walls, Gothic sacristies, and Baroque chapels.

Wikimedia

The Modern Perception of Cathedrals

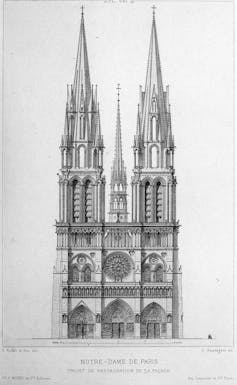

It was in the 19th century that people began to see cathedrals as timeless and immutable. Figures like Viollet-le-Duc crystallized this idea, imagining an original state for buildings that never actually existed and undertaking restorations that, rather than recreating the original, added new transformations.

Despite modern desires to "recreate the identical," cathedrals remain products of centuries of change and adaptation. The real question, then, is what we want our cathedrals to become. The answer to this question should guide the technical and artistic choices in their restoration.

Maxime Fulconis, PhD (Ecole Doctorale Mondes Ancien et Médiévaux) , Sorbonne University

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original version in French.