The origins of the modern Olympics

Interview with Alexandre Farnoux

Illustration: The Soldier of Marathon announcing victory 1834, Cortot © 2021 Grand Palais Rmn (musée du Louvre)/Franck Raux

The roots of the Games

On the eve of the Paris Games, the exhibition Olympism - a modern invention, an ancient heritage explores the roots of the first Olympic Games at the end of the 19th century. Alexandre Farnoux, co-curator of this exhibition at the Louvre, professor of Greek archaeology at Sorbonne University and former director of the Ecole française d'Athènes, sheds light on the sometimes misguided link between the present-day games and their Greek ancestors.

What led you to become co-curator of this exhibition?

Alexandre Farnoux: It all began in 2015. While stationed in Athens, I was contacted by the last descendant of the Gilliéron family - a Swiss family living in Greece - who suggested I recover their archives. This family of painters and restorers had worked with archaeologists to draw, restore and study all the graphic documentation of the great archaeological discoveries in Crete and Greece from 1880 to the Second World War.

The material recovered was vast, including manuscripts, graphics, photographs, tools, casts, prints and more. I working alongside Christina Mitsopoulou, an archaeologist at the French School in Athens and researcher at the University of Thessaly. We discovered a set of documents relating to the refounding of the modern Olympic Games in 1896: sketches for posters, coins, banknotes, stamps and postcards, made by Émile Gilliéron, appointed by the King of Greece as the official designer of these first Games in Athens.

I wanted to turn this personal interest into a collective project through this exhibition.

The French School in Athens

Founded in 1846, the French School in Athens (École française d'Athènes) was the first foreign research institute in the humanities. Initially linked to the Villa Medici, it is dedicated to the practical study of Hellenism through field analysis of sites described in ancient sources. Part of a network of five French schools abroad, it offers internships, research grants and secondments to students, PhD students, post-docs and teachers for in situ research visits. It has several excavation houses, equipped with state-of-the-art equipment (drones, lidars, etc.) and a scientific staff including topographers and restorers, as well as a vast library and an extensive scientific archive service.

The Exhibition

How did your research activities influence its design?

A. F.: For the 2004 Athens Olympic Games, I had been working on the archaeology of sport and had accumulated a vast amount of scientific material on the sporting practices of the ancient Greeks, which I had never used before. With Violaine Jeammet, chief curator at the Louvre, and Christina Mitsopoulou, we set up a project combining our complementary expertise and this archaeological material in relation to the history of modern Olympism, drawing on the archives of Émile Gilliéron.

We presented our project to the President of the Louvre in 2022, who gave us the go-ahead to create this exhibition on Olympism.

What do we discover in this exhibition?

A. F.: The aim of the exhibition is to show how the modern Olympic Games have been inspired by ancient sources, sometimes even distorting or manipulating them. In particular, it shows how the Louvre's collections influenced the creation of modern Olympic iconography through the sketches and drawings of Émile Gilliéron. Inspired by the Greek objects he discovered in the Louvre's galleries during his studies at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, he left his student file with drawings of reliefs and vases from the museum, which he then used to create stamps, medals and trophies.

In addition, we wanted to highlight little-known aspects of Olympism in this exhibition, and in particular the way in which this international phenomenon, which today is highly commercial and stereotyped, actually stems from the humanities, knowledge produced by scholars and scientists. While Pierre de Coubertin is widely recognized, other important figures, such as Michel Bréal, a leading French intellectual, linguist, Hellenist, a pacifist activist and educational reformer, are often overlooked, despite their crucial role. Yet it was Michel Bréal who, from deep in his library, re-invented the marathon race, now run by millions around the world.

The exhibition also reveals how 19th-century prejudices were misleadingly projected onto Antiquity. We show, for example, how Pierre de Coubertin's exclusion of women was based on a manipulation of ancient sources. Contrary to what he claimed, women took part in sporting competitions in Antiquity, notably at Olympia in honor of the goddess Hera.

The last room of the exhibition explores the creation of Olympic iconography and its detour over time. Can you tell us more about this?

A. F. : In conjunction with the National museum on the histroy of immigration, which presents a political history of the Games, we wanted to give the public the means to understand, analyze and criticize the stereotypes associated with Olympism today.

Many images have been exploited for political and commercial ends, distancing modern Olympism from Pierre de Coubertin's original intentions. The Olympic flame is a striking example. Although torchlight races existed in ancient times, they only covered short distances for religious rituals. The aim was to light the fire to cook the sacrificial meat. In 1936, the flame was reintroduced for the Berlin Games, manipulated by Nazi Germany for Aryan propaganda purposes. Today, it's surprising that this symbol with its problematic origins should be retained, when other controversial elements, such as the Olympic salute, inspired by the salute to the Roman senate and hijacked by Fascist Italy, were abandoned after the Second World War.

The image of Myron's Discobolus, now pre-empted by modern Olympism as the quintessential representation of ancient sport, also raises questions: in 1938, Mussolini sold the best known copy to Hitler as a symbol of the Aryan race.

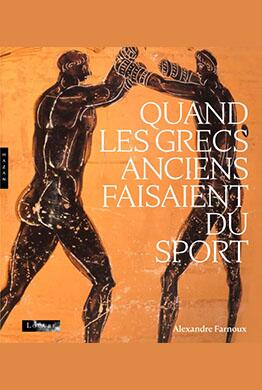

You've just published the book Quand les Grecs anciens faisaient du sport (When the ancient Greeks did sports). What do we learn about the ancient Greeks' relationship with sports?

A. F.: In this book, I explore how the collections of the Louvre and other ancient sources reveal a completely different vision of sporting practice in ancient Greece, far removed from our modern concepts. For the ancient Greeks, training was a matter of health and balance. Sport was also closely linked to military practice. Citizens, conscripts, infantrymen and horsemen, aged 18 to 50, had to be ready to defend their city. Physical activity was a political act. This civic responsibility was also reflected in men's tombs, where sports training equipment was sometimes found.

It was not by accident that the Hellenist Michel Bréal proposed the creation of the marathon race as a symbol of the victory of democracy. Inspired by the battle of Marathon (490 BC), during which Athenian citizens defended their freedom against tyranny, this race offers a political model for the sport, which was to produce healthy citizens ready to defend freedom and democracy.

Finally, let's not forget that in ancient times, competition was a religious act: the Greeks competed to honor the gods together. The important thing was to participate, not to establish records and rankings. This represents a clear break with the contemporary world, where the notion of performance has become central over time.

Alexandre Farnoux

A specialist in Minoan Crete and Delos, Alexandre Farnoux is a Professor of Greek Archaeology at Sorbonne University's Faculty of Arts and Humanities and Honorary Director of the École Française d'Athènes, having served as its Director from 2011 to 2019.

Alexandre Farnoux has been fascinated by archaeology since his early teens, and was drawn to field research. As a student, he worked on a variety of archaeological sites in France, England and Poland, covering periods from prehistory to the Middle Ages. At the same time, he developed an interest in ancient languages, which naturally steered him towards Greek archaeology and art history. He earned an agrégation in classics and a bachlor’s degree in archaeology before entering the École Normale Supérieure.

His thesis at the École Française d'Athènes in the late 80s marked the start of his career in Greece, where he continues to work regularly. His daily life, between Paris and Athens, combines the study of ancient texts, teaching and archaeological excavations close to the sources.

Crédits photo © Christophe Averty