Omicron, a Different Form of Epidemic

Interview with infectiologist Karine Lacombe, professor at the Sorbonne University Faculty of Medicine and head of the infectious and tropical diseases department at Saint-Antoine Hospital, Paris.

Since the spring of 2020, France has experienced five waves of infection due to SARS-CoV-2 and its different variants since 2021. What is the situation in the country today? What is the effect of the arrival of Omicron, both on hospitalizations and for children? And how has the hospital adapted the management of Covid patients? Read an analysis and perspective by Prof. Karine Lacombe, infectious diseases specialist and Head of the Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases Saint-Antoine Hospital, Paris.

The Conversation-France: In France, what is the status of the waves linked to the different variants of SARS-CoV-2?

Karine Lacombe: Since November 2021, we have been in a fifth wave where the Delta variant was in the majority. It manifested by an increase in infections, which were coupled 15 days to 3 weeks later with an increase in hospitalizations. The number of hospitalizations and admissions to intensive care units reached a high plateau during the Christmas period. There were 245 critical care admissions per day in mid-December, 285 at the end of December and 345 at present.

And, specific to the present sequence, even before there was an inflection of the contaminations and especially of the occupation of the intensive care units, we saw the emergence in mid-December the arrival of Omicron with a kind of sixth wave overlapping the previous one. Since the end of December, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of infections, but this has not yet translated into hospitalization: for the time being, the patients who arrive in our departments are mainly Delta patients.

We are performing combined PCR tests on hospitalized patients to detect, among others, SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses. For the moment, influenza is not yet too prevalent, but it will inevitably increase. And in case of co-infection, how will Omicron behave? The flu? Will both viruses cause symptoms? We don't know.

T.C.: It's still early days, but what can you already observe about the Omicron variant?

K.L.: It is possible that this variant has different properties than its predecessors, such as extreme contagiousness and clinical signs that are not exactly the same. There are also specificities at the patient level: on the one hand, we have patients with Delta who arrive at the hospital clearly with Covid... and others who arrive with various pathologies and in whom we discover, when they arrive at the emergency room, the unnoticed presence of Omicron. In their case, we can't really talk about a Covid, since Covid is a disease with well-defined symptoms (the main one being a hypoxemic pneumonia, i.e. requiring high oxygen needs) and here absent, but rather of an asymptomatic carriage.

So for the moment we have another form of epidemic than simply a new wave. But we are at the very beginning of this sixth sequence, so it is difficult to see where it will lead. However, we have the examples of England and South Africa, which would have already passed its peak and where it seems that Omicron has caused fewer serious forms of Covid. In England, at the moment, out of ten people who arrive in the emergency room with Covid, one goes to intensive care; where usually it's one in five... That's why we sometimes hear that it's half as pathogenic.

Why is that? To the intrinsic properties of Omicron... or to the fact that 75 percent of the population is vaccinated (90 percent in France)? It is still too early to say, we will have precise statistics in two weeks.

T.C.: Are there already data concerning the symptoms of Omicron?

K.L.: The first clinical observations we have made are that Omicron tends to cause "high" forms of illness: pharyngitis and laryngitis, sore throats reminiscent of strep throats, runny noses... Things that affect the ENT sphere, and not the deep lung, unlike Delta. Among vaccinated people, especially those who have received three doses, we have many asymptomatic carriers or those who develop rare symptoms over two or three days - like a kind of flu, with a bit of a sore throat, sometimes a bit of fever, aches and pains and then it passes.

Still, we should be cautious: In the last week of December, 14 percent of people hospitalized for Covid in the ICU here had Omicron.

Another point is that we have 500 children hospitalized in France for Covid (we don't yet know if it's Omicron or Delta), the highest number we've had - and 80 percent have no comorbidities. Which is proportionally normal: with several hundred thousand people getting infected every day, children are bound to be affected. But in this case, it is an epidemic that has been spreading like lightening in children and in young adults.

And there is the issue of PIMS (pediatric multisystemic inflammatory syndrome) that can affect children three to four weeks after their Covid. There have been a few cases with the other variants, what will happen with Omicron? This is something that is of concern, and we won't know more until February or March. (Between March 2, 2020, and December 26, 2021, 826 cases of PIMS were reported, 745 of which were related to Covid-19. The number of cases has been increasing since the end of November, according to Santé publique France (France Public Health).)

T.C.: With such a spread of Omicron and the diffusion of the vaccine, will we reach the collective immunity regularly put forward?

K.L.: Perhaps, by necessity... But it would not be a homogeneous immunity: there would be different levels within each population group, because immunity acquired by vaccination is more solid and lasts longer than that acquired by exposure to the virus - and even more so when one is vaccinated after infection. Nevertheless, this should help to slow down the spread of the epidemic - unless at some point a new variant emerges that completely eludes our immune system.

That's what we're seeing with Omicron, since it takes three doses to get it under control and people infected with other variants and not vaccinated are easily reinfected.

T.C.: You have indicated that the increase in infections has not (yet) been accompanied by an increase in hospitalizations. Has the management of patients changed in two years?

K.L.: We have indeed made a lot of progress: we now adapt the type of treatment to the profile of the patient and the stage of the disease at which he or she is.

In simple terms, we consider that Covid has two phases: a viral phase, which starts two to three days before the onset of symptoms and lasts three to four days afterwards; then an inflammatory phase, where the virus is less present but the patient develops an exacerbated inflammatory response. The drugs developed target these two phases.

At the beginning of the epidemic, since we had patients in the inflammatory phase, we focused on evaluating drugs capable of "breaking" this reaction, since it is the runaway of our immune defenses that leads to resuscitation. The first drug that really showed its effectiveness was a corticoid (dexamethasone). Others then played on the modulation of the immune response.

This made it possible to reduce mortality in intensive care by two: before, it was as high as 30 percent, but now it is more like 15 percent.

Then, we made progress in the treatment of the viral phase. Normally, when we are exposed to the virus, naturally or by vaccination, we develop antibodies capable of recognizing the intruder and guiding our immune response. However, some people do not have antibodies and are at risk of severe forms of the disease: for example, immunocompromised people - and non-vaccinated people.

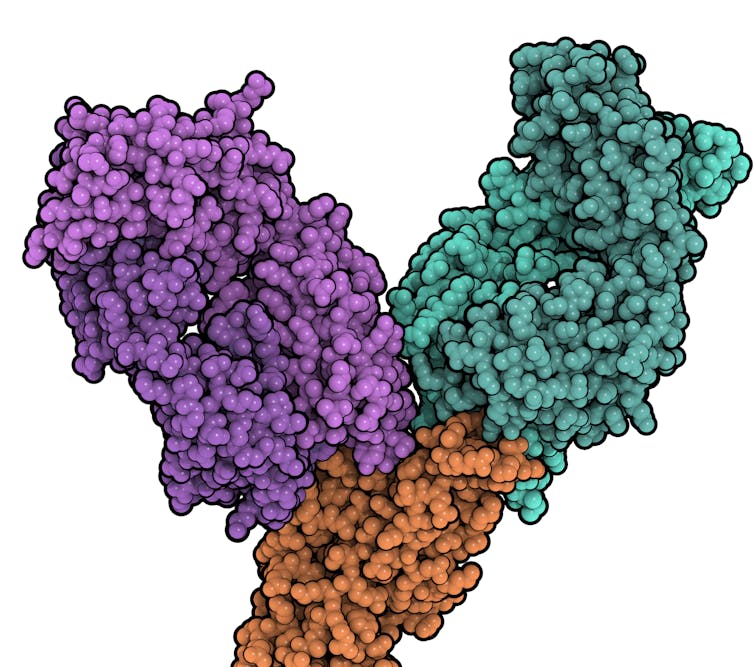

Treatments capable of mimicking the action of these antibodies have been developed, the most successful being monoclonal antibodies (created in the laboratory against a specific target, in this case the Spike protein). Authorized for use in immunocompromised patients, they reduce the risk of hospitalization by 80 percent if symptoms occur during the first five days of the disease.

Unfortunately, several of these monoclonal antibodies (such as Ronapreve), which are very effective against the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 and previous variants, including Delta, no longer work on Omicron, whose Spike has changed significantly due to mutations (Evusheld remains partially effective).

When a patient arrives at the hospital, a serological analysis is always performed to look for the presence of antibodies. If there are no antibodies, monoclonal injections can be proposed.

Another type of antiviral exists, but with less established efficacy. One has not been approved for early access in France (MSD's molnupiravir), and the other (developed by Pfizer) is under review. The data are not yet published and scientifically evaluated, just announced in press releases.

T.C.: Are there any preventive treatments?

K.L.: The best one is of course the vaccine, which protects from severe forms those who can, physiologically, make antibodies. And those who cannot, can receive monoclonal antibodies. For these vulnerable populations, including immunocompromised people, they can be injected as a preventive measure - this is pre-exposure prophylaxis (before being exposed to the virus) or immediate post-exposure prophylaxis.

They are also used for early treatment within five days of the onset of symptoms. After these five days, if you are still ill, a severe form of the disease, particularly of the lungs, is developing. We then resort to immunomodulators and corticosteroids.

T.C.: How are the hospitals still preparing to cope?

K.L.: We have started again to deprogram surgical acts... but it is more and more difficult: staff has left, exhausted, leading to the closure of beds. We are fighting again on a daily basis to reinvent solutions. For example, by trying to accelerate the discharge of patients by getting them to rehabilitation centers, temporary retirement homes or Covid homeless centers, etc., according to their needs, so that the beds can be emptied and new patients taken.

Or beds are "diverted" from certain units by changing their destination. For example, in sectors dedicated to check-ups (diabetes, cardiovascular...), we will bring all the necessary equipment (respirators and others) to transform them into intensive care units adapted to Covid.

But on the one hand, this means that the care and analyses of the patients initially programmed in these units are postponed, by one month, three months... And on the other hand, it is very complicated logistically speaking, and physically and nervously exhausting for the caregivers. Another concern, with such a contagious Omicron, is the work stoppages due to infection. Fortunately, with the compulsory vaccination of the caregivers, there are no serious forms, but quite a lot of personnel stopped.

With this variant, it is perhaps not so much the seriousness of the disease as the disorganization of society that is likely to follow that will be the main problem.

T.C.: Looking back, how do you see these two years?

K.L.: Today, with each new wave, we have to deal with new unknowns: how will the vaccinated people resist, which clinical signs will dominate, how to transform additional beds for resuscitation procedures... But in 2020, we lived through something unimaginable and we just missed a terrible catastrophe.

We managed to cope because we stood together. Both at the hospital, where very strong ties were created and which continue despite the fatigue, and with the population that, whatever one may say, was very involved. In one year, for example, 90% of the population has been vaccinated: who would have thought it? We don't realize the logistical effort that such a level of vaccination represents for the population, which has itself accepted the injection.

We tend to underestimate this because those who make the most noise are the noisy minority who are against the vaccine and those who give disinformation. Overall, we all went in the same direction.

We have been confronted with an unprecedented crisis, which has affected us mentally, physically, socially... But I think that when we come out of it and look back on these three years, even if our democracy has been strained, we will come out with our heads held high.

If I have one big regret, it is the difficulty of fighting disinformation. In the name of freedom of expression, we have allowed sites to continuously broadcast false information. We can disagree on certain things but, at some point, we cannot go against scientific knowledge established collegially. I am not talking about the victims of this fake news, who are then found in our services, but about those who promote them often for economic or personal reasons and who abuse the vulnerable public who listen to them. We have not been able to deal with this.

Karine Lacombe, Infectiologist, Head of the Infectious Diseases Department at Saint-Antoine Hospital, Sorbonne University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article in French.

![]()