A Brief History of the Long-Standing Mistrust Between the French People and the Elites

The history of contemporary France can be viewed through various prisms, but one of the most relevant is that of the tumultuous relations between the people and the elites.

In the long stretch of history from the Revolution of 1789 to the present day, moments of communion between them are rare: the Fête de la Fédération of 1790 (the predecessor of Bastille Day), the July Revolution of 1830, the Spring of 1848, the political truce known as the Sacred Union in 1914, the post-war Poincaré government from 1926 to 1928 and the return to power of Charles de Gaulle in 1958.

All of these rare moments followed serious crises – that of the absolute monarchy in the 1780s, the reactionary turn under Charles X, the blindness of King Louis-Philippe and his main minister François Guizot in the 1840s, the uncertain entry into World War One, the painful exit from it, the crisis of the Fourth Republic and the Algerian War. Even then, it’s impossible to speak of total unanimity in the nation: there were always resisters, outcasts and scapegoats among the people and within the ranks of the elites.

These enchanted parentheses almost always closed quickly, either because the new leaders did not manage to resolve the crisis at hand, or because the people felt they were not being understood, the hopes they had placed in the elites betrayed. Sometimes, the elites or a counter-elite help to close the parenthesis more quickly. Rarely did they benefit from their own success in the long term.

The elites always come out on top

France has undergone thirteen major political changes since 1789, and yet there have been very few major changes to the country’s elite, despite an undeniable but slow process of democratisation.

The sequence from 1815 to 1848 is particularly emblematic. Only those who paid a certain amount of tax were eligible to vote and run in elections, and the gap between the “legal country” and the “real country” was very wide. Out of 29 million French people in 1816, there were just 90,000 voters and 16,000 eligible to run.

Casimir Perier by Louis Hersent, Château de Versailles, 1827

The landed gentry who had dominated the Restoration were swept away by the July Revolution of 1830, carried out by the bourgeoisie with the help of the Parisian people, but the latter quickly became frustrated. The July Monarchy relied mainly on high ranking civil servants and business owners – symbolically represented by the regime’s first two heads of government, two bankers: Jacques Laffitte and Casimir Perier.

In February 1848, the monarchy and its great notables were overthrown in their turn by the petty bourgeoisie and the Parisian people. The latter were once again soon frustrated. Following a conservative turn in the government and a series of victories in legislative elections, the ruling elites of yesterday were returned to power by 1849.

The origins of mistrust

Mistrust of the elites is not specific to France, as shown by the populist victories of the past ten years in Great Britain, Italy, Eastern Europe and the USA. People largely distrust their leaders because of the results of globalisation, the remoteness of supranational institutions, the power of big tech companies and the associated economic and social crises from all of the above. The fact that they have been made a spectacle of by the media for the past 40 years and the hypercritical gaze of social networks do nothing to help matters.

But the French mistrust comes from much further back: it starts with a centralised and over-inflated state, an all-powerful bureaucracy, the almost exclusive training of the elite in the same select institutions and a tendency to intellectualise problems which, sometimes, simple common sense would allow to be better addressed.

And while France seemed to go against the tide of populism by electing Emmanuel Macron over Marine Le Pen in 2017 – admittedly on the promise of a new world, new faces and new practices – distrust was not long in resurfacing on a large scale, as witnessed by the gilets jaunes movement, the massive strikes in response to pension reform or, more recently, the protests against the vaccine pass.

New crisis, new training ground

At each major crisis in post-Revolutionary French history, the people have questioned the role of the institutions that train the members of the elite.

France’s “grandes écoles” – its most prestigious academic institutions – were created during the French Revolution. In 1800, the Conseil d’État was founded to act as a nursery for the senior civil service, and in 1848 the meritocratic École Nationale d’Administration (ÉNA) was established, but quickly abolished to return to the previous system of nepotism and clientelism.

The École Libre des Sciences Politiques (today known as Sciences Po) and the École Supérieure de Guerre were set up in the aftermath of the 1870 Paris Commune, and after the Second World War, ÉNA was refounded at the same time as the Institutes of Political Studies and the corps of civil administrators.

Today, in response to the gilets jaunes protests, Emmanuel Macron has decided to abolish ÉNA, which has become more and more cut off from the reality of French life over time. Macron, a graduate of the school, announced it would be replaced by an Institute of Public Service – designed to be more socially open and more adapted to the needs of France.

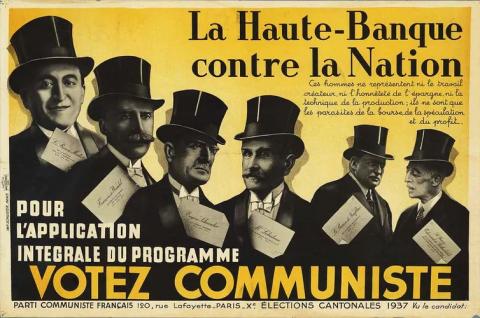

The search for scapegoats within the elites is also a very French trait: today, the ÉNA graduates known as “enarques”; under the Revolution, the aristocrats and the priests; at the end of the 19th century, parliamentarians and Jews; in 1914-18, the war profiteers; in the 1930s and under the Vichy regime, once again the parliamentarians, the Jews and the “200 families”. Always, the rich.

‘ The High Bank versus the Nation. PCF poster stigmatising bankers François de Wendel, Eugène Schneider, Jean de Neuflize and Édouard de Rothschild (1937 cantonal elections). zoomable= Wikimedia, CC BY

A very French paradox

The mistrust of the elites may have a long history in France but today, in an age of extreme media coverage and immediacy, the associated defeat of intelligence is worrying. Genuine intellectual debate all too often disappears in favour of ersatz ideas dominated by the one-track thinking and the politics of offence.

What a long way we have come from the Enlightenment, where Rousseau said to d’Alembert: “What questions I find to discuss in those you seem to be solving” and even from the great disputes between Jean-Paul Sartre and Raymond Aron.

The disappearance of one of our greatest intellectual journals, Le Débat, shows the extent of the impoverishment of thought.

The French people are far from blameless in all this: don’t we get the elites we deserve, especially since the introduction of universal suffrage?

This is the conclusion of some foreign observers, including that of American scholar Ezra Suleiman, who has long studied this country. He diagnoses “a schizophrenic tendency” among the French to demand everything and its opposite: an aspiration for hierarchical power that must be exceptional, infallible and virtuous on the one hand, and a passion for equality, a desire for proximity to the elites, and a thirst for freedom on the other.

Eric Anceau is an Associate Professor of History at Sorbonne University.

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.